3 - The Presocratics (3) - Heraclitus: Before the Cave

On Heraclitus, a man who sought to give us the tools to decipher to complex world that existed in front of us

Audio Available Here (Free for everyone for this post only)

Creatures of a day! What is man? What is he not? He is the dream of a shadow […]

Pindar, Pythian Odes 8.94-951

Mankind, for much of history, can be described as sheep — believing in the social narrative that was written by the same society which seeks to gain something from them. Yet, one philosopher, Heraclitus, sought to bring those who would listen to some singular truth in regard to the world around them.

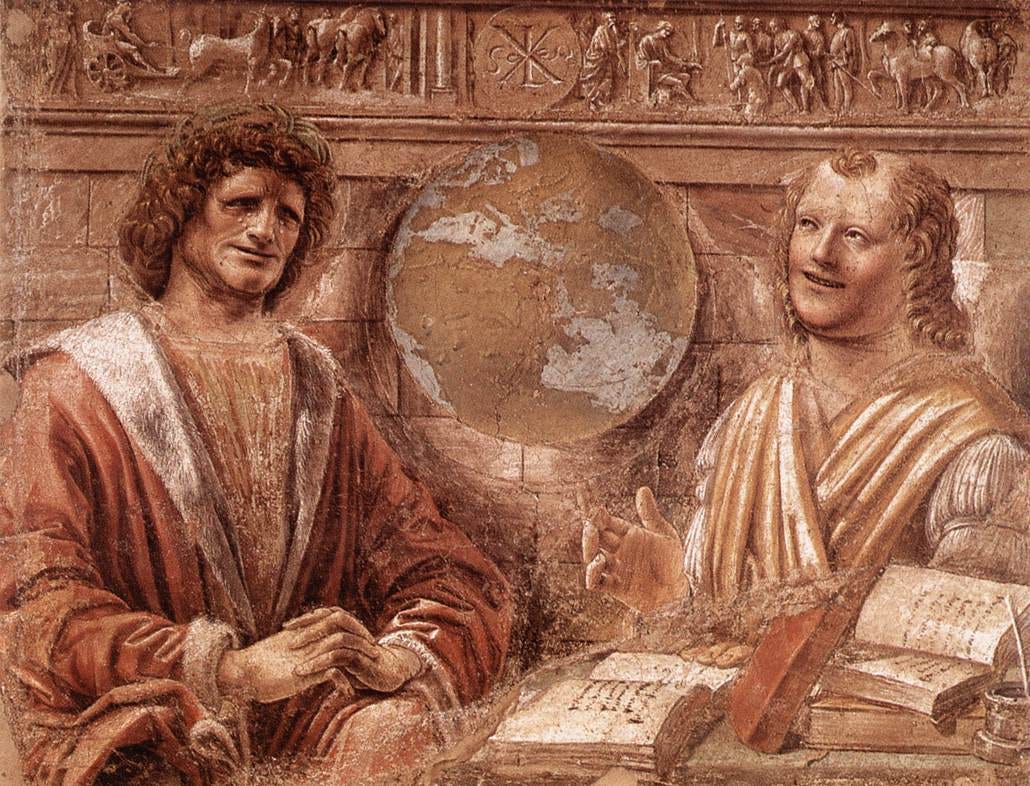

Heraclitus lived sometime around the mid-500s to the mid-400s BC, though specific dates are not at all known. This would put him as a younger contemporary to Xenophanes and Pythagoras, but most likely born sometime after the Thales and Anaximander’s death (and born right around when Anaximenes was a very old man). Heraclitus was born in the coastal Ionian city of Ephesus, upon the same continent as all of our other philosophers so far. Ephesus would be north of Miletus (where the three original philosophers lived), southeast of Colophon (where Xenophanes was born), and northeast of the island of Samos (where Pythagoras was born).

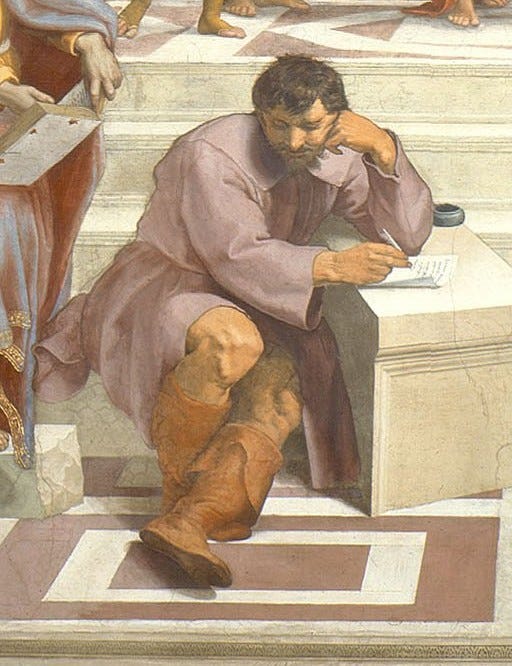

Heraclitus’ philosophy was born from the fact that man’s natural tendency was to follow the easy road and to believe what was told to them. He stated that “In their ignorance after having listened they behave like the deaf. The saying ‘Though present they are absent’ testifies to their case” (Heraclitus, Fragment 5, from Clement’s Miscellanies). And even worse, despite that fact that men often act as sheep and listen to what they are told without proper critical thought about why this person or governing body is telling them this, they refuse to admit in any way that they are not fully aware of the reality in which they live: “the majority of people live as though they had private understanding” (Heraclitus, Fragment 6, from Sextus Empiricus’ Against the Professors). Ideas such as this can be seen through the ages of future philosophy and literature ranging from the not too distant ‘Allegory of the Cave’ within Plato’s Republic to contemporary writers like Thomas Pynchon or Roberto Bolaño — a hidden world lying outside one’s line of sight, but which could be revealed if one were willing to look, and if one possessed the proper tools. Heraclitus, thus, is the first western thinker who we see bring this ideology to light. The Milesians were more concerned with what made this world up rather than some greater Truth, Xenophanes was more concerned with our view of the Gods and of our inability to ‘Know,’ and Pythagoras was more concerned with mathematics in a similar ontological vein as the Milesians. But here, we see our first seeker of true Truth.

However, saying he was a ‘seeker’ is disingenuous, for while it is possible (though unlikely) that he knew the answer he was trying to convey, his philosophy (or, at least what we still have of his philosophy), was more used as a methodology to teach his readers how to come to this Truth themselves.

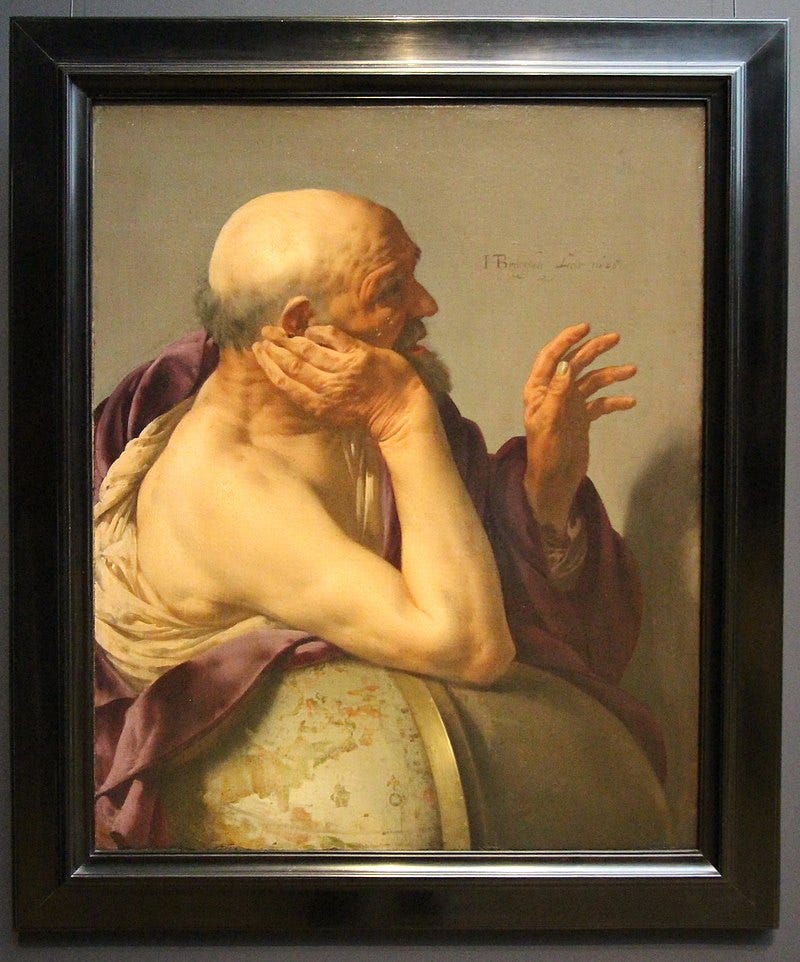

To start, Heraclitus stated that “Eyes and ears are bad witnesses for men if they have souls which cannot understand their language” (Heraclitus, Fragment 27, from Sextus Empiricus’ Against the Professors).2 He believed that our standard use of mankind’s senses could never provide a sufficient observation of our reality in order to attain this singular Truth — a truth which he called logos.3 But how does one achieve this truth — this logos, this Word, this principle — beyond our mere senses? Unfortunately, there is not much we can do, for even Heraclitus who apparently has these answers admits that “The things I rate highly are those which are accessible to sight, hearing, apprehension” (Heraclitus, Fragment 28, from Hippolytus’ Refutation of All Heresies). He understands that the senses are all that we have and that everything we can have knowledge of us must come via one of these many senses. The issue with our use of these senses, however, is not that we must learn to unlock some mystical ‘sixth sense,’ but rather that we refuse to apply our mind to the senses that we already possess to analyze what have always traditionally used them for — the expected: “If you do not expect the unexpected, you will not find it, since it is trackless and unexplored” (Heraclitus, Frament 9, from Clement’s Miscellanies). You must, like Plato’s brave soul within the depths of the Cave, unshackle yourself from what you have always been comfortable and familiar with. You must go beyond that which is purposefully presented to you as a ‘shadow on the wall,’ for if all you ever hear or see is what is expected, then the unexpected (the logos) will pass you by without even having to stay silent.

Luckily, Heraclitus, did not believe that this revelation could only occur within the minds of ‘Great Men,’ stating that “Everyone has the potential for self-knowledge and sound thinking” (Heraclitus, Fragment 31, from John of Stobi’s Anthology). Hence, his purpose in what we contemporarily consider his most important fragments — those which were meant to open our eyes to the methods we should use to seek this reality. However, even though all men can understand facets of the logos, no man can understand all: “You will not be able to discover the limits of souls on your journey, even if you walk every path; so deep is the principle it contains” (Heraclitus, Fragment 48, from Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of Eminent Philosophers). It is a similar epistemological take like Xenophanes and Pythagoras presented but builds on them via the previous fragment (F 31) stating that we do have the capacity for true knowledge — just not complete knowledge.

What is it, then, that we are supposed to be searching for? First, we must understand that “The true nature of a thing tends to hide itself,” (Heraclitus, Fragment 25, from Themistius’ Speeches) and that in regard to ‘harmony,’ “non-apparent is better than apparent” (Heraclitus, Fragment 24, from Hippolytus’ Refutation of All Heresies). In other words, we are seeking hidden metaphors for a hidden reality. Today, it is not uncommon to hear people questioning the purpose of metaphor and symbolism in art. Literature which verges on the incomprehensible or at least that is incredibly difficult to interpret is always questioned as to the purpose — must Thomas Pynchon use such seemingly pointless digressions? why do Deleuze and Guattari employ such incomprehensible metaphors in their work? is James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake impossible to fully understand? And if so, in reference to the final example, which it likely is, then what is the point? Well, the point — both in regard to the final example and the previous ones — is to extrapolate reality into a series of metaphors that can in turn reveal facets of reality which exist beyond the literally sensorial. Yes, we are still using our natural senses to interpret what we are hearing or seeing. However, now that the metaphorical is being introduced, our intellect is being challenged in a way that it naturally would not. If we can thus make metaphorical, symbolic, or allegorical connections between what we see or hear day-to-day and that which exists within the deeper recesses of our mind, then perhaps logos will eventually be realized. These branching paths would eventually lead to the epiphany that Heraclitus wants us to realize — the epiphany of Fire: fire being both his version of a First Principle and the symbol he uses to explain logos which we can see when he says “Everything is a compensation for fire and fire is a compensation for everything, as goods are for gold and gold for goods” (Heraclitus, Fragment 38, from Plutarch’s On the E at Delphi).

Knowledge of this fire/logos proves that

[…] people prove ignorant, not only before they hear it, but also once they have heard it. For although everything happens in accordance with this principle [logos], they resemble those with no familiarity with it, even after they have become familiar with the kinds of accounts and events I discuss as I distinguish each thing according to its nature and explain its constitution.

(Heraclitus, Fragment 1, from Sextus Empiricus’ Against the Professors)

Put otherwise, often when the metaphor is made — when the unseeable realm is connected with reality or when logos comes fully to fruition — it is left as metaphor. No further strides are taken to push this metaphor forward into something more material. It is left as is — as symbol and nothing more. For fire, as a symbol, reveals much. It is literally immaterial, being built purely of energy, consisting of no actual matter. Thus, as a First Principle, it would be more akin to a soul than atomic theory. Are we all then built from an immaterial substance? And further, it rises and descends in temperature and in colors along the visible light spectrum. It engulfs and destroys as readily as it keeps us warm and makes our food both more delicious and safer to eat. It is beautiful and terrifying. It is magical and common. The sky has brought it to life in front of our eyes, and we have learned to act as the sky, bringing it to life to keep us warm. What else, then, could symbolize our existence? But it does not merely symbolize — it is far, far more. How can we understand this though — “How, from a fire that never sinks or sets, would you escape?” (Fragments, Heraclitus, trans. Brooks Haxton).4 Well, to escape the general sense of metaphor as metaphor, what better than to hear some more metaphors.

Thus, we finally get into the fragments which Heraclitus presented as his actual means to open his reader’s minds to the reality of existence — to teach us the means to find logos for ourselves.

The first and most well-known of these is when Heraclitus states that “On those who step into the same rivers[,] ever different waters are flowing” (Heraclitus, Fragment 33, from Arius Didymus) — or, in the common way that this fragment is told, ‘you can never step into the same river twice.’ First, we can see this occur within a material river. Let us take the most globally familiar river: the Nile. If one were to stand at its western edge at the exact moment that I am writing this sentence (2:47 PM, Pacific Standard Time on November 16, 2025) while another person was standing on the eastern edge at this same time, upon both stepping into the river, neither of us would experience the same rush. The waters that I touched would be from an entirely different origin than that which they touched. If I then stepped out of the water and stepped back in at the time I am writing this sentence (2:48 PM on the same day), then the waters I touched would be different from my companion’s and my own previous step. And if I came back a year later (2:47 or 2:48 PM — no difference which — Pacific Standard Time on November 16, 2026) to step back into this river on either side, it would be as different as any of these entrances before. On top of this, we could have stepped in at various points — not merely east and west of each other, but at the mouth end or the other end, at either side, in the middle, or upon tributaries. However, independent of location, it has always been the Nile. Is there an answer as to which of these views are correct?

The answer is that all exist at once. This is simultaneously a monad, a duality, and a plurality. But not just in the sense of the river. It can be applied to so much more. History, for example, has readily been described as a vortex. It circles and circles again, repeating itself in iterations that are synonymous with past events, and yet which concentrate into far more destructive and horrible versions with increasingly evolved technologies. Thus, when a genocide one year is attempted or rendered successful, the same methods will be used a century later, achieving the same goal but in a completely different, more ‘perfected’ sense. The river has once again been entered, but its waters have evolved — stemmed from some other origin or purpose. And of course, Heraclitus was likely not writing this fragment with the intention of metaphorizing genocide or possibly even history. But one could see how this metaphor could be applied through various realms of human experience, rendering something we once knew solely through our typical sensorial analyses to something far greater and more important.

What other metaphors did Heraclitus similarly utilize for this same purpose?5 Firstly, within a testimony by Aristotle, it was said that “The sun, according to Heraclitus, is new each day” (Aristotle, On Celestial Phenomena). Could this be in reference to where we awake? the angle of the sun when it arises in reference to our home? How the sun or our Earth have rotated in the last twenty-four hours? or even the composition of the sun itself given the nuclear reactions which have gone on within it?

And another: “It makes no difference which is present: living and dead, sleeping and waking, young and old. For these changed around are those and those changed around are again these” (Heraclitus, Fragment 13, from Ps.-Plutarch, Letter of Consolation to Apolonius). In reference to this fragment, what constitutes living and dead? Are we referencing the carbon versus non-carbon-based entities? Or that which has once been dead and is now living versus that which once lived and now does not? And what does it mean ‘to live?’ The same goes with sleeping and waking — for, both of these things are literal or can be read as metaphors for various states of mind. Similarly, can young and old be ages, states of mind, places in life, and so on.

And, again, another: “Road: up and down, it’s still the same road” (Heraclitus, Fragment 14, from Hippolytus’ Refutation of All Heresies). As I write this on Division Street in Portland, Oregon, I see those walking up and down it, some going east and some going west, now, in the past, and an hour ago. It is raining today — around fifty-four degrees Fahrenheit. But when I wrote at this same spot, even in the same chair, looking out at the same street merely three months ago, the day was warm, the sky was sunny, the people walked, and perhaps I even saw — without my knowledge — some of the same people. Are things the same today as they were then? or before I lived in this city? Well, the street is the same just as the Nile has never changed. But which realm of reality has altered never to be seen again, or which has concentrated itself into a new and more terrible or beneficent point in our existence.

And, once again, another: “Sea: water most pure and most tainted, drinkable and wholesome for fish, but undrinkable and poisonous for people” (Heraclitus, Fragment 15, from Hoppolytus’ Refutation of All Heresies). What constitutes poison versus sustenance? Does it depend on the elixir? they who are consuming? both? Could this elixir be metaphorical to law? governance? or even something as specific as humility?

We can keep going. Another: “The beginning is the end” (Fragments, Heraclitus, trans. Brooks Haxton). Need I explain this one? Need I go on?

The point is made. These metaphors — these fragments of philosophical thought — are meant to lead the reader or listener to find their own path toward discovering logos. Toward discovering fire. Heraclitus gave those who would listen the tools to unpack reality beyond what they were told reality was. Without his tools, the person would fall back into base sensorial experience and would, at the same time, follow the shepherd as they always had done. To this, Heraclitus would have said (did say, really),

What use are these people’s wits, who let themselves be led by speechmakers, in crowds without considering how many fools and thieves they are among, and how few choose the good? The best choose progress toward one thing, a name forever honored by the gods, while others eat their way toward sleep like nameless oxen.

(Fragments, Heraclitus, trans. Brooks Haxton)

In the end though, how much can we fully trust our most eminent and revolutionary philosophers? For even they can falter. Heraclitus, unfortunately, was within his own ‘cave.’ There is no doubt that he himself would have admitted that he was not immune to bias — that he himself still failed to understand some aspect of fire, of logos. His faltering existed in the realms of law and in governance, for he believed a number of things which merit massive criticism. Firstly, he stated that “One man is worth ten thousand, as far as I am concerned, if he is outstanding” (Heraclitus, Fragment 55, from Theodorus Prodromus’ Letters). Heraclitus, like many that would follow him even unto today, believed in the theory of the ‘Great Man.’ Was, for instance, the destruction of Hiroshima or Nagasaki justified if it would maintain the Western Empire or those who ran it? Is a person without a home less worthy to survive than one with? or even one who led an academic life? Similarly, Heraclitus stated that “The people must fight in defense of the law as they would for their city wall” (Heraclitus, Fragment 53, from Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of Eminent Philosophers). But again, why is his specific society’s law all of a sudden considered to be the logos of which he told us to seek? What constitutes the law of Ephesus greater than that of Samos, or Miletus, or Colophon, or modern-day China, or Afghanistan, or America, or Libya, or Chile, or Somalia? And even, with some objective series of ethical methodologies, one was to discover the utmost just forms of law and governance, who is to say that one should be willing to die for such a thing? Is a form of governance of this sort not supposed to do for us what we could not do for ourselves? And if so, what is the justification for death to maintain this if death is what we are supposed to be protected from?

Finally, through a testimony, Heraclitus is said to have believed that “Souls slain in war are more pure than those which die through illness” (Heraclitus, Testimony 10, from a Bodleian scholiast on Epictetus). Why must I die for a society whose only purpose of existence is to render those like me to live a more just life? If it was merely me (or you) who died for all else in the city, then it would make more sense. If it was even five or ten of us, then I would cede the point. But if one army must be formed to fight an army who believes their form of law is more worth dying for than the other, how can we prove otherwise? How can a single one of these fighting souls be classified as more worthy than a person who is pinned to their deathbed through no series of events that they have molded on their own?

Plato’s ‘Allegory of the Cave’ would not be written for another ~120 years, but its origins find themselves here. Heraclitus posed a new realm of epistemological thought, taking us from the material that is presented to us to the material which is hidden away. If we are told by one like Thales that the material world is built of water, or that by Xenophanes that God is an omniscient, omnipotent, non-anthropomorphic being, what tools do we have to say otherwise? One of these may seem, today, absurd. The other has genuine merit. But could these be mere metaphors for what the philosophers were attempting to get across? And if not, then we must utilize our extra-sensorial means to parse these claims so to make better sense of our own reality outside of what their literal words are telling us. But even those like Heraclitus himself falter. So, what is there to do? If the man who pioneered this philosophy — this methodology — was as similarly unreliable as we are, then why would we trust him? Well, despite the necessary tendency to distrust men who led to our modern western empire, Heraclitus did give an objective methodology to analyze this world outside of his own erratum. He likely knew that his political and material thought could similarly be subject to the same biases as those whom he was trying to teach. But hopefully, with his tools, bias such as his or ours would be able to be rooted out, exculpated, analyzed, and, eventually, realized and changed.

Up Next: Parmenides

Pindar. The Complete Odes. Translated by Verity Anthony, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Quotes cited as such are from the Oxford World’s Classics edition of the Presocratic Philosophers:

The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and the Sophists. Translated by Robin Waterfield, Oxford World’s Classics, 2000.

The Penguin Classics version of Heraclitus’ Fragments (translated by Brooks Haxton) unfortunately translates logos as ‘The Word.’ If you have that copy (which is one of the copies of his works that I have) make sure you cross that out and replace it with logos. The copy of The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and the Sophists which I have mostly been using through this series so far, uses logos in the explanatory texts but then within the translated fragments and testaments, retranslates logos as ‘the principle.’ Do the same for that one.

Quotes cited as such are from the Penguin Books edition of Heraclitus’ Fragments:

Heraclitus. Fragments: The Collected Wisdom of Heraclitus. Translated by Brooks Haxton, Penguin Books, 2003.

I won’t go as in depth with the coming metaphors as I did with the ‘river’ metaphor for fear of just being redundant. However, you should be able to see how the river metaphor is similar to the others and how this can be applied to reality.